Can you repeat that?

We now discuss what a computer does best: repeat something over and over again. The looping mechanism, or ability to repeat, allows a computer to perform mindless tasks time and again that would otherwise render you bored to tears. Let me repeat again: repetition is good.

Looping with for

One of the looping mechanisms most programming languages provide is the for statement, otherwise known as the for loop. In JavaScript, the for statement is structured as follows:

1

2

3

for (initialization; condition; update) {

// run code

}

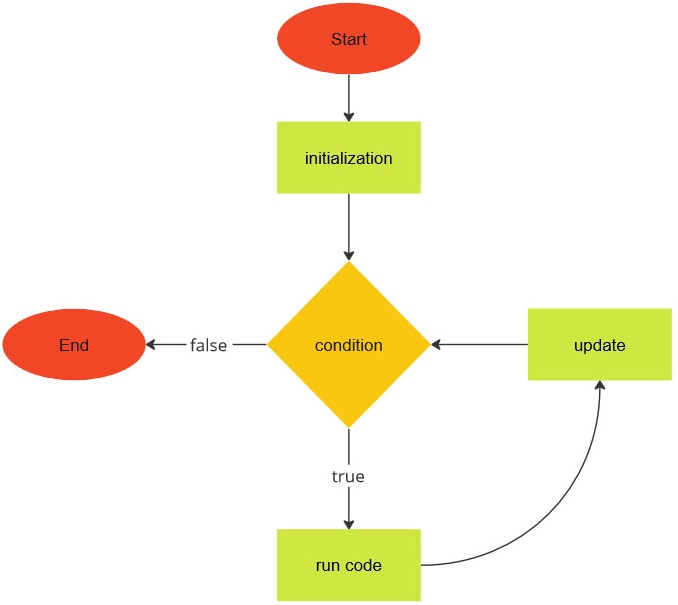

The structure of the for loop is illustrated in the image below:

The initialization is an expression that is evaluated before the loop begins. You often want the initialization to declare a variable whose sole purpose is to be the loop counter. The condition is an expression that is evaluated prior to each iteration of the loop. The condition should evaluate to a boolean. If the condition evaluates to true, then code within the loop body would be executed. In case the condition evaluates to false, the loop ends and execution picks up from the first code statement following the closing brace } of the for statement. Finally, the update is an expression that is evaluated at the end of each iteration of the loop. The update typically increments (or decrements) the loop counter.

Let’s use a simple example to help us understand the above description of the for loop. Consider the following program to output the integers from 0 to 9 to the terminal.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

/**

* Print 10 integers to the terminal.

*

* @param {NS} ns The Netscript API.

*/

export async function main(ns) {

const max = 10;

for (let i = 0; i < max; i++) {

ns.tprintf(`${i}`);

}

ns.tprintf(`Printed ${max} integers.`);

}

The initialization is the expression let i = 0. The condition is the expression i < max, where the variable max has been declared to hold the integer 10. Finally, the update is the expression i++. Prior to entering the first iteration of the loop, the condition i < max is evaluated to determine whether it results in a true value. The value of i is initially 0, hence the expression i < max evaluates to true. We now enter the loop body for the first time and the code inside the loop body prints the value of i to the terminal. We have executed all code we can within the loop body, so we now evaluate the update expression i++. The expression increments i by 1 and i now takes on the value 1. Control then jumps to the condition again, where we evaluate the expression i < max. Again the expression evaluates to true because 1 is indeed less than 10. We enter the loop body for the second time, print the integer 1 to the terminal, and the update expression increments the variable i to 2. Control jumps to the condition and we repeat the above process. The loop ends when i < max evaluates to false, which occurs when i holds the value 10. The last value of i printed to the terminal is therefore 9.

Let’s make the above program more interesting. Let’s modify the program to sum all integers from 0 to 9, inclusive. You need a variable to keep track of the cumulative sum. Declare such a variable outside of, and before, the loop. No need to modify the initialization, condition, and update portions of the loop. Each time you enter the loop body, you add the value of i to the cumulative sum. The program below should do what we wanted.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

/**

* Sum of integers from 0 to 9, inclusive.

*

* @param {NS} ns The Netscript API.

*/

export async function main(ns) {

const max = 10;

let sum = 0;

for (let i = 0; i < max; i++) {

sum += i;

}

ns.tprintf(`Sum is ${sum}`);

}

The keywords let and const

In the script sum9.js , why did we declare max as const max and sum as let sum? Why not const max and const sum? Or let max and let sum? When you use the keyword const to declare a variable and immediately assign a value to the variable, JavaScript prohibits you from reassigning the const variable. It does not matter if you reassign the same (or a different) value to the const variable. Think of const as constant. A constant does not change its value. Thus max is a constant. (Does that mean max is a constant variable? Sounds like an oxymoron does it not?)

Being the inquisitive learner that you are, you modify the program as follows:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

/**

* Sum of integers from 0 to 9, inclusive.

*

* @param {NS} ns The Netscript API.

*/

export async function main(ns) {

const max = 10;

max = 11; // <-- Error here.

let sum = 0;

for (let i = 0; i < max; i++) {

sum += i;

}

ns.tprintf(`Sum is ${sum}`);

}

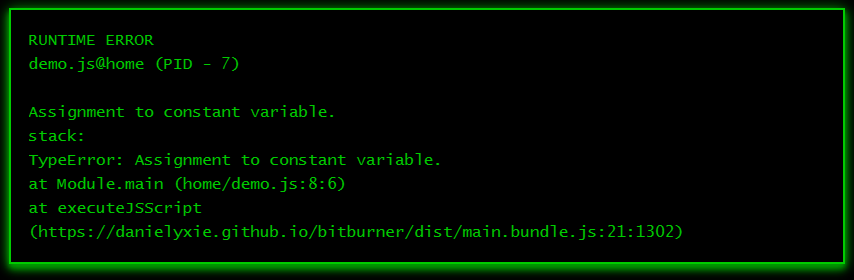

You execute the modified script. Then Bitburner (and ultimately JavaScript) yells something like this at you:

Hey, didn’t you give

maxthe value10and told me that you don’t want to change the value ofmax? Why are you givingmaxa different value now? Can’t you make up your mind? That’s it. I quit.

That is not really far from the truth. JavaScript does not like the modified program, gives you the cryptic message shown in the image below, and stops running the rest of your script. A variable declared using const should stick to one and only one value.

Let’s talk about let. A variable declared with the keyword let can have its value changed. That is it, really. Short and sweet.

Looping with while

While we are on the topic of looping, let’s consider another means of repeating things in JavaScript. The while statement is structured as follows:

1

2

3

while (condition) {

// run code

}

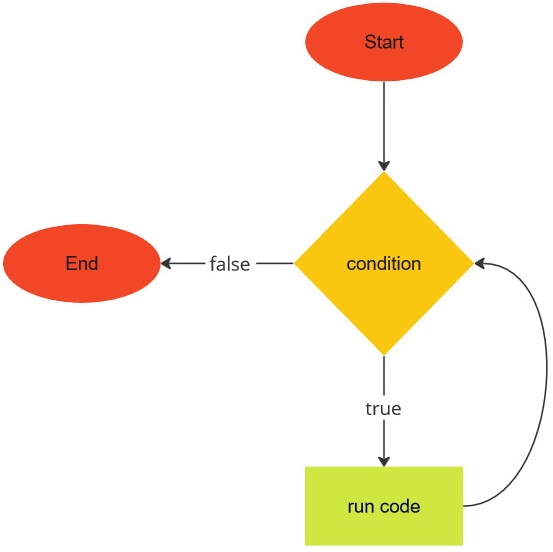

The structure of the while loop is illustrated in the image below:

The loop body is delimited by the open brace { and closing brace }. The condition should be an expression that evaluates to a boolean. First, the condition is run. If the condition evaluates to true, then code within the loop body would run. If the condition evaluates to false, execution would jump to the code after the closing brace. After running code within the loop body, the condition would be evaluated again. If the condition evaluates to true, the above process would be repeated. Otherwise the loop ends.

The for and while loops are similar to each other, so similar in fact that you can convert code written using one loop statement to code that uses the other loop statement. By way of example, consider the script for-int.js above. The for loop of the script can be written using a while loop like so:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

/**

* A while loop equivalent of for-int.js.

*

* Print 10 integers to the terminal.

*

* @param {NS} ns The Netscript API.

*/

export async function main(ns) {

const max = 10;

let i = 0;

while (i < max) {

ns.tprintf(`${i}`);

i++;

}

ns.tprintf(`Printed ${max} integers.`);

}

String along some characters

Let’s use the while statement to process strings. Recall that each string has the length property, which counts the number of characters in the string. Each character in a string is associated with an index, an integer starting from 0. The next character has an index that is 1 greater than the previous character. The maximum index of any character in the string is the value of length minus 1. The following illustrates the relationship between the string "abcdef" and the index of each character.

1

2

0 1 2 3 4 5

a b c d e f

The first character a has index 0. The next character is b, which has index 1, etc. The last character f has index 5, which is 1 less than the number of characters in the string.

Suppose you declare a string like so const s = "Mississippi";. As M is the first character, its index is 0 and you can access this character like so s[0]. Notice the index is between the opening [ and closing ] square brackets. How would you access the second character? The second character has index 1 because indexing in JavaScript starts from 0. The second character can therefore be accessed as s[1].

How would you use the string index to count the number of times the character "i" appears in the string "Mississippi"? You iterate over each character one at a time. If k is the current index, then the character at index k is s[k]. Compare s[k] with "i". If the result of the comparison is true, then you know that "i" occurs at index k. Otherwise "i" does not occur at index k. Increment the index k, move on to the next character, and perform the comparison. Repeat the above process until you have considered all characters of the string. How do you know when to end the process? The maximum index of the string is the value of the string property length minus 1. Use this fact as your loop condition. Here is a program that counts the number of times the character "i" appears in the above string.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

/**

* Count the number of times i appears in a string.

*

* @param {NS} ns The Netscript API.

*/

export async function main(ns) {

const s = "Mississippi";

let k = 0;

let n = 0; // Count number of i.

while (k < s.length) {

if (s[k] === "i") {

n++;

}

k++;

}

ns.tprintf(`"i" occurs ${n} times`);

}

Exercises

Exercise 1. Read more about the for and while loops here and here.

Exercise 2. JavaScript has the do...while statement as a third means of looping. In some cases you might find this looping mechanism useful if you need to execute some code at least once. Read more about the do...while statement here.

Exercise 3. Use a while loop to rewrite the script sum9.js .

Exercise 4. Use a for loop to rewrite the script mississippi.js .

Exercise 5. Use a for loop to write a program that sums all integers between 1 and 100, inclusive. Provide a while loop equivalent of your script.

Exercise 6. Print the following pattern to the terminal.

1

2

3

4

######

######

######

######

Do so in three different ways. One of them must not use a loop.

Exercise 7. Use a loop to output the following pattern to the terminal.

1

2

3

4

5

#

##

###

####

#####

Exercise 8. Use a loop to print the multiplication table (from 1 to 12) to the terminal.

Exercise 9. The factorial of a positive integer $n$ is defined as $n! = 1 \times 2 \times 3 \times \cdots \times n$. Use a loop to calculate the factorial of 10.

Exercise 10. Write a program to calculate the sum of all numeric digits in the string "3141592653".